George III by Sir William Beechey. RCIN 405422 ©

1772-1778

The period from July 1772 to September 1778, and consequently the correspondence in George III’s Calendar of official papers, marks a more turbulent time in George III’s reign. These papers deal with America’s fight for independence, which gained traction in this period, and the issues which were directly and inadvertently caused by this, namely relations with European powers such as France and Spain, a near-constant reshuffling of Government, and discontent in Ireland.

A large proportion of the documents are written to George III, primarily by members of his government including Prime Minister Lord North, Lord Rochford, and Lord Sandwich. The collection also contains drafts of letters written by George III (again, primarily to his ministers), and reports sent to him from the House of Commons. These often detail the bills passed in the House and issues discussed, such as the ‘Boston Port Bill’, the ‘Bastard Children Bill’ or the resolution on the East India Company (which was deemed to be out of control and in need of reigning in).

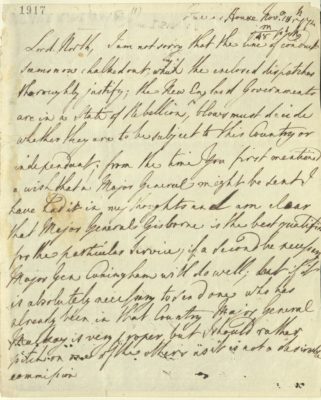

George III to Lord North on the ‘State of Rebellion’ of the New England governments, November 1774. RA GEO/MAIN/1917 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

In this correspondence, the rising tensions in America caused by issues seen in previously published documents, such as the Stamp Act, come to a breaking point. Arguably, the final straw for North America comes in the passing of the Boston Port Bill which, as Lord North wrote to George III in 1774, ‘past the House without a division but after a pretty long debate’. This act intended to close Boston Port until the tea dumped into the harbour by the Rebels in 1773 was paid for. Instead, it fuelled revolutionary spirit. Later that year, the comptroller and collector in Rhode Island wrote to the Commander of HM’s Customs at Boston informing him that the American people were in a ‘Spirit of Opposition’ towards the customs officers. He noted also that the general assembly had ‘lately passed an Act for purchasing 300 Barrels of Gunpowder, 3 Tons of Lead, 40,000 Flints and 4 brass field pieces to be deposited in the Town of Providence’.

In a subsequent memorandum, George III noted ‘the serious crisis to which the disputes between the Mother Country and its North American Colonies are growing’ due to their ‘ill-grounded claims’ for ‘total independence of the British Legislature’. The following year, the King informed Lord North that ‘the line of conduct now seems chalked out…the New England government are in a State of Rebellion, blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this Country or independent’. This arguably marks the point of no return for both George III, and Britain as America’s metropole.

The stages of the American War can be traced through this correspondence; for example, letters such as George III’s to Lord Sandwich of 11 January 1776, detail both the ‘Vigour…shown by the Rebellious Americans’ and the worrying, surprising slowness of his navy, while the King’s letter of 17 December 1776 reported that the Rebels had nearly been driven out of New York. Some discussion of offers of peace are also evident in the correspondence, such as the proposals made by Lord North in 1778 .

The events in America sent a ripple all over the Western world, which is also apparent in the official correspondence of the King. Spain, France and the Netherlands all became supporters of America in its revolution, causing deterioration in relations between Britain and these significant powers, which, in the case of France, led to the Anglo-French war. A number of the letters in the collection provide intelligence on the movements of European vessels, possible plans against British forces, and reports of attacks. Thomas Mant, also known as Mr. M., was one of the intelligence-gatherers who appears in the papers, however, most of his correspondence contains requests for more money rather than useful information for the British (it would later emerge that Mant was a double-agent in the pay of the French).

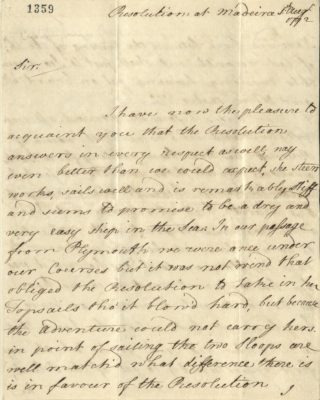

Letter from Captain James Cook, 1 august 1772. RA GEO/MAIN/1359 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth 2019

The instability felt in Britain itself is also clearly reflected in this range of correspondence. The primary example is the ongoing reshuffling of Parliament, and Lord North’s constant pleas to resign. After several tentative letters of resignation to the King, Lord North wrote in March 1778 that, if the ‘load of important duties is any longer entrusted to him, National disgrace and ruin will be the consequence’. George III still appeared reluctant to allow him to resign (Lord North remained Prime Minister until 1790), despite the fact that doubts were cast on Lord North’s capability by other ministers.

The question of the leader of the American Department (i.e Secretary of State for the Colonies) was one which was also problematic. The position was vacated several times during a decade and was difficult to fill. Several other government roles also had to be filled by George III after they were vacated in this period. The instability and ineffectiveness of George III’s ever-changing administration was evident through its reception amongst the people. In 1773, George III received a ‘Copy of the City Remonstrances’, in which the Aldermen and Livery of the City of London stated that:

the many Grievances & Injuries We have suffer’d from Your Ministers still remain undressed, nor has the Publick Justice of the Kingdom received the least Satisfaction for the frequent atrocious Violations of the Laws, which have been committed in your Reign, by Your Ministers

GEO/MAIN/1517

Despite the fact that much of the correspondence perhaps does not reflect positively on this stage of George III’s reign, there are several reminders that this era was one in which literature, art and discovery flourished. For example, Captain James Cook writes to George III from aboard the Resolution in 1772, in a letter where he reveals that a woman had sneaked aboard the ship disguised as a male botanist in order to be with Joseph Banks. She left on finding out he was no longer on the Resolution.

In another example of the more cultural aspect of the papers, in 1772, Samuel Foote, notable Georgian actor, petitioned the King to be allowed to keep the Haymarket theatre open all year. He had recently had a successful run there of a play called ‘The Nabob’, a satire on the East India Company which, as evidenced by this collection, was a rather sensitive topic in government. George III did, as far as we know, not respond.

1778-1780

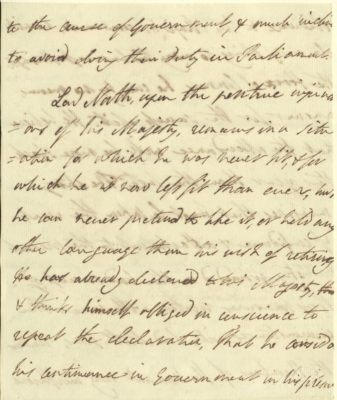

Lord North to George III offering his resignation, 10 November 1778. GEO/MAIN/3108-3110 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

The documents in George III’s Calendar dating from October 1778 to December 1780 comprise roughly one thousand documents. These cover a very politically troubled and unstable time for George III and Britain, in terms of both domestic and foreign affairs. The papers give an insight into the rivalries and ill will within Parliament, the discontent of the people culminating in the infamous Gordon Riots, and Britain’s loosening hold on its colonies.

In 1778, the British government still had Lord North at its helm. Towards the end of the year, it became clear that the government was unravelling; by October, Lord North complained “of the slackness of the attendance given by the members of Parliament and the little assistance he did receive by those who did attend”, and of a general lack of support, which he predicted would only worsen. Lord North deplored that “principal & most efficient offices are in the hands of persons who are either indifferent to, or actually dislike their situation”, and he was arguably proven right by the several resignations received by George III, which continued to weaken the government. These included continued attempts by Lord North to resign, claiming he had never been fit for the role, such as GEO/MAIN/3108-3110. He was also clearly an unpopular Prime Minister in this period demonstrated by assassination plots and plans to overthrow him to personal disagreements with figures such as Alexander Wedderburn, the Attorney General.

The correspondence does gives an impression of a government heading towards reform in this period with Lord North talking of “strong measures” to improve the state of government and its relations with members of Parliament. Conversely, plots were clearly afoot to overthrow Parliament, with Charles Jenkinson suggesting that the destruction of government had been discussed. In consequence of the slew of resignations and a general desire to remove oppositional or lacklustre ministers, George III was frequently in conversation with Lord North and other ministers concerning the men best suited to roles in the government and the army. One letter from the King to North from July 1780 shows particularly interesting rhetoric concerning a proposed coalition, suggesting that members of the opposition “who come into Office must give assurance that they do not mean to be hampered by the tenets they have held during their opposition”, to ensure that the coalition is not simply “a patch, to secure Elections in the new Parliament”.

Members of Parliament and government officials were not the only members of society who were displeased. There are signs throughout the correspondence of restlessness and discontent from the public, with whom “the Opposition are not popular nor the Ministry neither, & the nation is gloomy, & displeased at their present situation“. This ill feeling towards government and King came to a head in early June 1780 as riots spread through London. The Gordon riots were a product of rising resentment towards government, but more importantly and blatantly, years of anti-Catholic sentiment brought to a head by the Catholic Relief Act of 1778.

The Gordon Riots are named after Lord Gordon, an MP born into the Scottish nobility who was fiercely defensive of Protestantism and a vocal supporter of American independence. Having successfully blocked the Catholic Relief Act in Scotland, Gordon amassed an impressive 40,000 names on a petition which he took to Parliament. Having arranged for a huge group of followers to gather in Westminster on 2 June 1780, the mob soon became riotous, first destroying Catholic buildings, then moving on to more widespread destruction including attacks in the Moorfields area and on public buildings such as the Newgate and Fleet prisons. Much of the infamous actions of the Gordon Rioters are described in the correspondence which includes reports of an attack on Lord Sandwich and threats to the home of Lord Kenwood, as well as relevant Cabinet minutes and an enquiry into the riots. During the course of the insurrection, the government debated whether it should reconsider Lord Gordon’s petition, but eventually sent in the army to deal with the rioters. In the aftermath of the Gordon Riots, the government made an unconventional choice to spread the executions of the chief rioters around London, as GEO/MAIN/3908 shows, so as not to give supporters a place to congregate and reignite the riots, while also acknowledging that the bodies of those executed should not become “objects of compassion or even veneration”.

‘Neck or Nothing’. A satire on the American War of Independence Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Britain was not only in turmoil on the domestic front, but also in terms of her colonial interests. The papers show that new colonies were acquired, but for the most part the correspondence documents the struggle to keep those already under its rule. George III made it clear that ‘Dependencies’ such as Ireland should not be listened to in their calls for independence, for fear that “opening the Door encourages a desire for more which if not complied with causes discontent and the former benefit is obliterated”. George III asserted that colonies were not simply a form of revenue, but that their compliance to British rule keeps Britain “from a state of inferiority and consequently falling into a very low class among the European States”, for “if we do not feel our own consequence other nations will not treat us what we esteem ourselves”. The American War of Independence remains a backdrop throughout the course of the correspondence in this period. There is an element of optimism in some of the letters, but for the most part they depict a Government largely opposed to the ‘unnatural’ war, and Britain turning to measures such as creating Loyalist militias, planning to recruit Native Americans, and granting letters of marque to privateers.