George III by Benjamin West, 1779. View image source

Copyright Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The official correspondence of George III (otherwise known as the Calendar) deals with the King’s role in the business of government. Many of the early papers – dating even before his accession as monarch in October 1760 – relate to the Seven Years War, foreign powers, and their military capabilities. Of these documents, many are notes on dispatches sent by officials based abroad reporting on the local situation. The original dispatches do not survive in this collection and instead George III has copied out the salient points by hand. In a small collection of reports from October/November 1769, we learn of a complaint against English privateers in Buen Retiro and a demand for compensation; that the king of Spain ‘seems not affected with ye loss of His Queen, but declares he will not marry again’; and most tellingly in the report from Paris that ’tis believ’d in France [that] ye death of ye late K. of England will prolong ye War’. George’s own thoughts and feelings on this matter are not recorded.

George is clearly conscious of the wider European context and he regularly receives reports from Sir Joseph Yorke on William V, Prince of Orange and the prince’s mentor Duke Louis Ernest of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also a relative of George III by marriage). These reports have a weather eye on who the prince will marry as George’s own sister Louisa was considered a possible match ” (Spoiler alert: she dies unmarried).”

George III took a keen interest in his Members of Parliament (MPs) as can be seen from the lists of Parliamentary representatives. The first of these 2 volumes was compiled around 1761 and includes constituency name, name of patron, occasional notes on family or personal connections or status (e.g. ‘West Indian’, ‘Surveyor of Mines’), and political allegiance. The King himself has updated the information over time.

For the most part, the Calendar consists of George III’s own drafts of letters sent to ministers; there are far fewer letters received and it is very likely that these papers were weeded out at some point probably being considered unworthy of permanent preservation – however much we may now disagree! Curiously, the bulk of the papers date from 1766 and after. It is not clear whether papers from early in the reign were not created in the first place i.e. that business was conducted face-to-face, or if they were subsequently destroyed.

Memorandum by George III on his actions relative to the Stamp Act [February 1766], GEO/MAIN/354 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The first decade of George III’s reign was characterised by warring political factions and civil unrest both at home and abroad – not least in the American colonies. In this memorandum written by George III in 1766, the King outlines his attitude towards the repeal of the much-loathed Stamp Act. Enacted in 1765, the Stamp Act imposed taxes in the British colonies and plantations in America and was designed to make the American colonists pay, at least in part, for troops that were stationed in North America following the Seven Years’ War. This meant that paper – such as that used for newspapers, books, and legal documents – had to have a stamp which was purchased from a government agent. The Stamp Act was widely despised in the American colonies and led to calls of ‘No taxation without representation’ as none of the colonies were represented in Parliament despite paying tax to the Treasury. Public reaction was so vociferous that Parliament was forced to reconsider the act and ultimately repealed it (although Parliament later enacted other legislation asserting its right to tax the colonies). George III himself was said to be in favour of repeal but this memorandum presents a more complex picture. The king believed in England’s right to tax its colonies but felt that the existing Stamp Act should be modified. He wrote,

From the first conversations on the best mode of restoring order & obedience in the American Colonys; I thought the modifying the Stamp Act, the wisest & most efficacious manner of proceeding; 1st because any part remaining sufficiently ascertain’d the Right of the Mother Country to tax its Colonys & next that it would shew a desire to redress any just grievances; but if the unhappy Factions that divide this Country would not permit this in my opinion equitable plan to be follow’d I thought Repealing infinitely more eligible than Enforcing, which could only tend to widen the breach between this Country & America.

GEO/MAIN/354

A fair amount of correspondence also passes in shoring up the Rockingham administration at home in 1766 and then the government led by the Earl of Chatham. In poor health, Chatham had repeatedly threatened to resign but remained following cajoling letters from the King. Following the dismissal of Sir Jeffrey Amherst a Governor of Virginia and the Earl of Shelburne, two of Chatham’s key allies, Chatham finally signaled his firm intention to go in a letter dated 12 October 1768.

My extremely weak & broken state of health continuing to render Me entirely useless to the King’s Service I beg Your Grace will have the goodness to lay Me, with the Request that His Majesty will be Graciously pleased to grant Me His Royal Permission to resign the Privy Seal

GEO/MAIN/854

Initially this was rebuffed by an unyielding George III:

The Duke of Grafton communicated to Me Yesterday Your desire of resigning the Privy Seal on account of the continuation of Your ill State of Health; as You entered upon that Employment in August 1766 at my own Requisition I think I have a right to insist on Your remaining in my Service; for I with pleasure look forward to the time of, Your recovery when I may have Your assistance in resisting the torrent of Factions this Country so much labours under

GEO/MAIN/829

Permission to resign was granted a few days later once assurances had been received that illness alone was the reason for Pitt’s resignation, not solidarity with his friends Amherst and Shelburne.

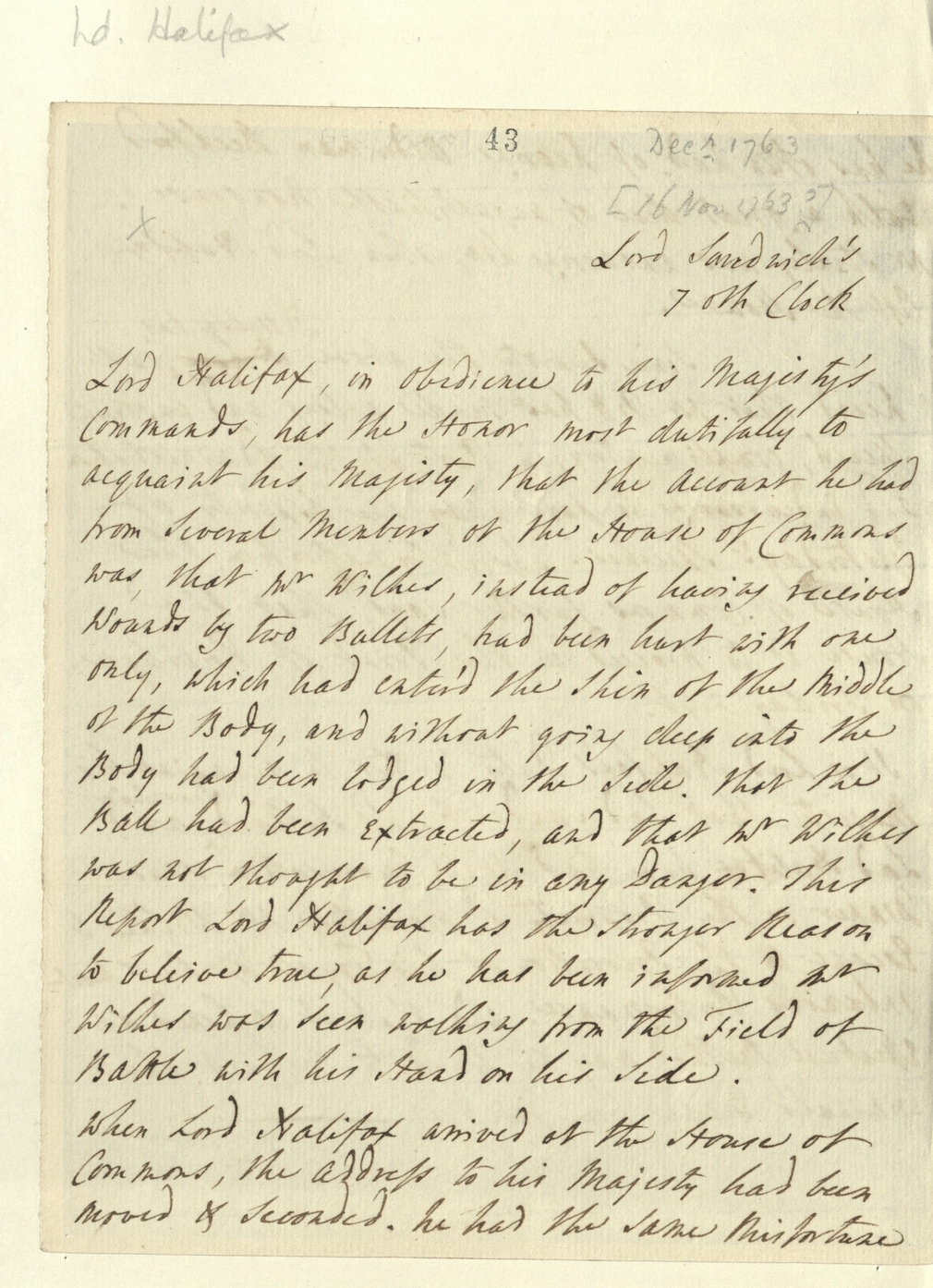

Lord Halifax reports on the duel between John Wilkes and Samuel Martin, [16 November 1763], GEO/MAIN/43 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

In terms of the letters received, these are typically reports from ministers on the day’s events in Parliament, particularly when controversial bills are being passed or when a crisis occurs such as the civil unrest by the Spitalfield silk weavers in 1765 and the response on restoring order. Questions on the right to parliamentary privilege, free speech, and the printing of Parliamentary debates all feature in these papers.

The figure of John Wilkes, the controversial MP for Middlesex, looms large, but silent, as there are no letters written by Wilkes to the King or any of the court surviving in this collection – if indeed they were sent at all. One of the first mentions of Wilkes is a reference to the duel he fought with Samuel Martin in November 1763 (both men survived). Writing in The North Briton (no 45), Wilkes criticised George III for accepting the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which concluded the Seven Years’ War; as a fierce patriot Wilkes regarded these terms as overly generous to France. Arrested on a charge of libel, Wilkes claimed Parliamentary privilege (immunity) by virtue of being an MP and fled to France on his release. However, in his absence, Wilkes was found guilty of seditious libel and outlawed; on his return, he was arrested and here we can read an account of his sentencing to imprisonment in June 1768. Protests following Wilkes’s conviction led to the unrest known as the Massacre of St George’s Fields in which several people were killed. These included William Allen, whose father later petitioned Parliament that justice had not been served; this motion was debated in 1771 but ultimately defeated. Popular among the people of the country of Middlesex, Wilkes was elected to the House of Commons several times but barred from sitting. However, this was not the end of Wilkes’s involvement in politics as he continued to make his presence felt in local politics until the end of the 1770s.