‘The progress of the Symptoms of the King’s Illness since November 1810, taken from the Reports of the Attending Physicians’, MED/16/15 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

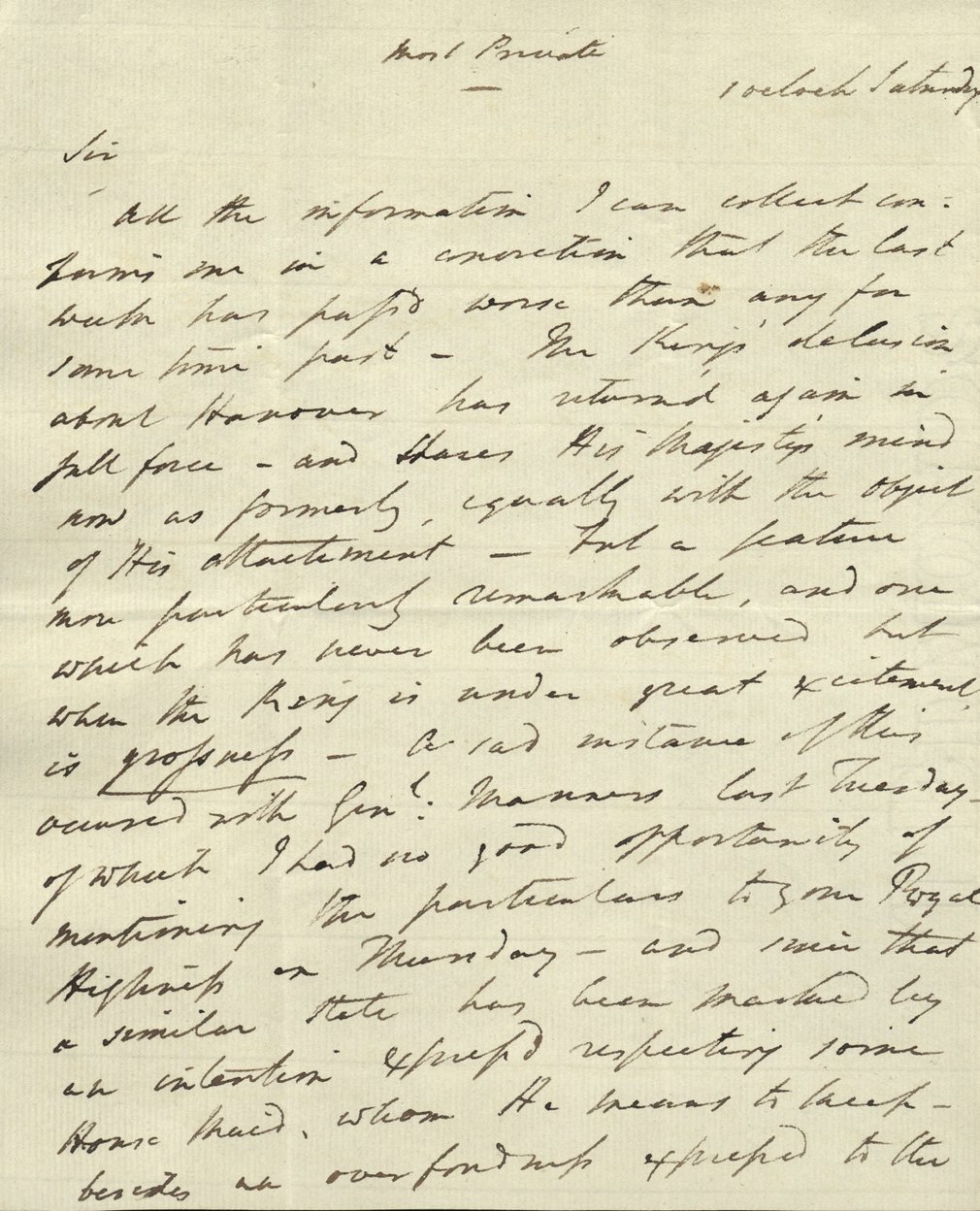

As may be expected, the historic papers relating to George III’s illness bear little resemblance to the formal documentation systems that are in use by the medical profession today. The bulk of the collection consists of letters written by the King’s Physicians to the Prince of Wales (latterly the Prince Regent) reporting daily on George III’s eating and sleeping habits – varying from anything between 30 mins to 7 hours – along with any notable changes or developments in the King’s behaviour. From 1810 until the middle of 1812, the majority of the letters to the Prince of Wales are from Sir Henry Halford, Physician-in-Ordinary to George III and many other members of the Georgian Royal Family. As such Halford’s letters make passing reference to the health of other family members, such as Princess Amelia in 1810 and Princess Sophia in 1813.

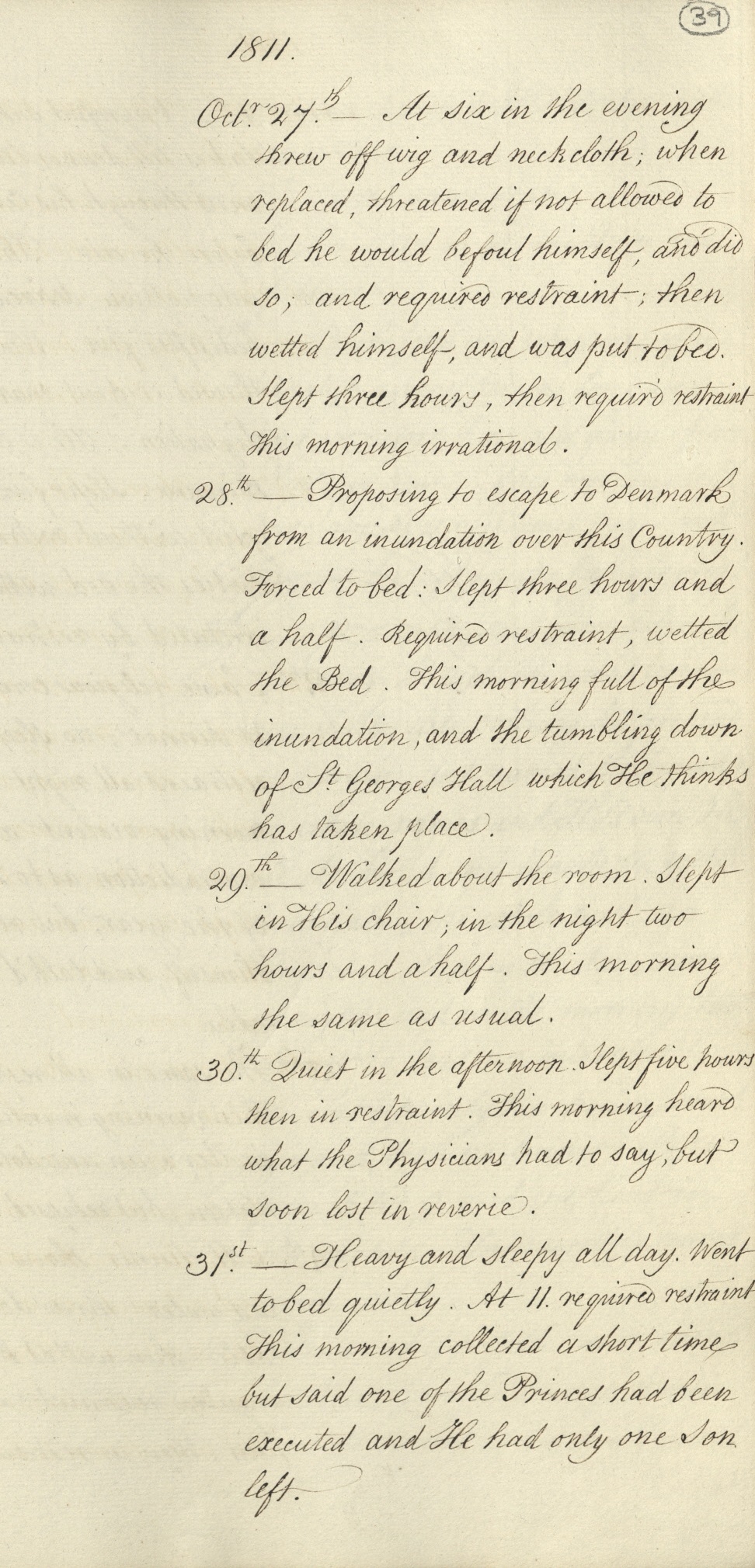

One of Halford’s journals from this period also survives covering 5 October 1811- 29 January 1812. Similar to the reports made to the Prince Regent, the diary contains substantial references to the mental illness of George III, referencing his delusions, swearing, need for restraint, lack of personal hygiene and removing his clothes. in addition to information regarding his pulse, medicines and other details of treatment such as the regular morning interview where the physicians challenged and attempted to correct the King’s ‘erroneous notions’. For example, there is frequent reference to a ‘ceremony’ conducted by the King, which appears to be a kind of communion, and is described here in an extract from November 1811:

H. M. said Grace audibly, & solemly, and then observed all the rest of his religious ceremonies deliberately crossing himself on the forehead & breast, & mentioning the Favorites [Lady Pembroke and Lady Caroline ?Damer] in whose names as well as his own, he ate the bread & drank the water & terminating the whole with an anthem. H. M. had not used any ceremonies of this kind the day before.

GEO/ADD/15/874

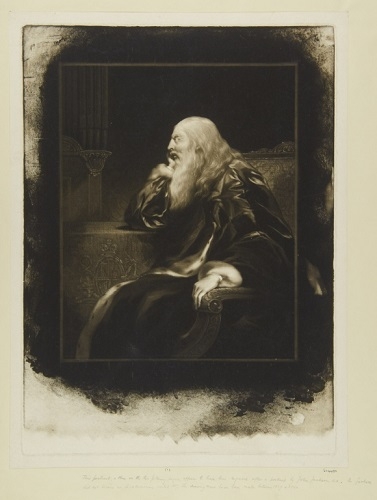

Samuel Reynolds (1773–1835) after Matthew Wyatt (1777–1862), George III (proof and finished states), published 24 February 1820. Mezzotint, 40.7 x 29.4 cm (plate). RCIN 604480 Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

One of George III’s delusions appears to be that he had the power to raise people from the dead and send people to the underworld. He also frequently held conversations with his ‘imaginary company’, those who were long-since dead including Princess Amelia. Writing 10 November 1811, Dr Matthew Baillie informs the Prince Regent: ‘[George III] had a long conversation with Princess Amelia as if she was in the Room with him, and gave her a minute account of all the particulars of Her Funeral’.

George III’s illnesses of 1788-1789, 1801, 1804, and from 1810 are not evenly reflected in the papers; in fact there are no papers at all here for the illness of 1801 and those for 1804 are copy letters only. Interestingly, the 1804 papers do include copies of answers to written questions submitted to the King’s Physicians by the Prince of Wales. Our understanding of George III’s initial illness in 1788-1789 can be augmented by the diary for this period of Robert Fulke Greville, Equerry to George III not least because this journal starts at the beginning of November (5th) whereas the surviving letters to the Prince of Wales are only present from later in the month (23rd). Robert Fulke Greville’s diary provides us with an eyewitness account of George III’s first illness as it unfolds. Regrettably, there are no similar diaries for the later illnesses.

Sir Henry Halford, 1839, after Henry Room. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

George III’s illness changed over time. In the last years of his life, the King seemed to become far more mellow, still clearly unwell and suffering from delusions but without such frequent outbursts of ‘passion’ that are mentioned in the early stages. The reports to the Prince Regent continue until George III’s death in January 1820 although they tend to become more formulaic over time, most likely there are fewer new developments to report. However, after the death of Queen Charlotte in November 1818, the Prince Regent rarely receives individual reports from the Physicians, instead receiving only copy reports that are sent to the Queen’s Council (later the Duke of York’s Council), the body charged with the management of the treatment of George III during his illness. Letters from the Physicians, Sir David Dundas in particular, appear only occasionally alongside the copy reports. How far these reports and those made to members of the Queen’s Council (such as Charles Manners-Sutton held at Lambeth Palace) complement, reflect, and contradict one another remains yet to be seen.

The role of George III’s daughters is highlighted in a handful of affectionate letters to Halford by Princesses Mary, Elizabeth and Augusta. In addition to describing the King’s symptoms and activities, these letters reveal the tensions behind the scenes and the real impact of this illness. Mary is a figure that has been traditionally overlooked being one of the younger sisters of 15 children and perhaps due in no small part to her notoriously difficult-to-read handwriting. Having nursed her younger sister Amelia through her last illness, Mary is also a key correspondent to the Prince Regent, for the period of George III’s last illness. The thousand or so letters written by Princess Mary to her brother between 1812 and 1816 provide an important insight into the impact of his illness on both George III himself and his family. These letters, as well as being informal medical reports, are also correspondence between royal siblings, and therefore, in addition, provide detailed information about Princess Mary’s life and royal happenings at Windsor.

Mary reported on George III’s health to her brother nearly daily; at times her letters were very short, simply communicating whether or not their father had been well that day, what treatment he had undergone or whether the King had shown any unusual behaviour. For example, her letter of 13 September 1812 simply read: “My dear Brother, more irritation has appeared today the King has talked a great deal & been very out of temper with his imaginary company this evening” (MED/17/2/24). George III’s ‘imaginary company’ were a regular feature of these reports. Mary sometimes found him in conversation with George I (MED/17/2/101), figures who had been dead for years, and sadly, the recurring figure of his young son Prince Octavius, who had died age 4 in 1783 (MED/17/6/41).

At times, the King appeared joyful – laughing and singing – and at other times, enraged, telling his doctors to go to hell and flying into such rages that he had to be carried to bed. At one point, he kicked down the dinner table and everything on it (MED/17/3/133), but other letters report that the King was completely himself and holding relevant conversation. George III even occasionally showed signs of hope that he would be declared well, even though he was never to recover for any significant period of time (MED/17/6/2).

Richard Cosway, Princess Mary c. 1795, Watercolour on ivory RCIN 420647: Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

The letters in which Mary describes George III’s moments of lucidity and his sadness at his own condition, when he is “sensible of his own deplorable situation” (MED/17/3/140) are particularly poignant. She eventually acquiesces that “nothing more can be done for the poor king but to prevent the health getting worse” (MED/17/6/177).

Mary’s medical correspondence is both unusual and fascinating in its ability to provide a different point of view in the study of George’s much-debated illness. She writes as a sympathetic family member, often capturing George III’s pathos, and conveying the effect of his illness on the family. One letter describes Queen Charlotte taking the “courage” to go and see her husband (something she did rarely and eventually not at all), and the joy it brought her (MED/17/1/114). Another letter describes her the King’s “horror” of his wife and Queen Charlotte’s reaction to it (MED/17/6/144).

Report on George III’s state of health by Sir Henry Halford, 16 March 1811, MED/16/2/17 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

What exactly was the ‘madness’ of George III?

In 1960s mother and son psychiatrists, Ida Macalpine and Richard Hunter, claimed that George III was suffering from the metabolic disorder, porphyria. While Macalpine and Hunter were given permission to consult the Halford papers held here in the Royal Archives, they did not see the daily reports produced for the Prince Regent now published online. A handful of researchers have subsequently seen these reports in recent years, namely Professors Timothy Cox and Martin Warren who support the porphyria diagnosis as well as Timothy Peters who rejects it in favour of bipolar disorder.

Any retrospective diagnosis is problematic. The historical record is not a clinical one or even necessarily a complete one; relevant papers may have been destroyed or lost, or if verbal reports were made, perhaps not actually written down in the first place. It is particularly unclear from the Physicians’ letters whether the behaviours noted are new developments or just a stronger presentation than usual. Symptoms may not have been correctly and accurately recorded or may have been as a result of the treatments given rather than of the illness itself; many of the treatments were experimental despite George III’s royal status. Then, as now, much remains unknown about the brain and psychiatry and the precise nature of George III’s illness and its causes is likely to prove inconclusive.