Princess Mary was born at Buckingham Palace on 25 April 1776, the tenth child and fourth daughter of George III and Queen Charlotte. Many of Princess Mary’s years before her marriage in 1816 were spent caring for members of her family; it was Mary who took primary responsibility for the care of her younger sister (and her father’s favourite), Princess Amelia. During their trip to Weymouth following Amelia’s illness in 1808, she assumed the role which is obvious in much of her correspondence; that of nurse, and intermediary between invalid and family. Princess Mary remained with Amelia until her death in November 1810, caring for her alongside her old wet-nurse, Mrs Adams.

Mary also remained at Windsor Castle during much of George III’s second bout of illness, which lasted from 1810 until his death in 1820. Again she acted as as a go-between for the royal family and the Prince Regent, reporting almost daily on her father’s health, but also relaying family gossip, arguments, and good news. This collection of correspondence can be found in the Georgian medical papers and dates from 1812 until she left Windsor on her marriage. The Princess eventually became Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh, with her marriage at the age of 40 to her cousin, Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, on 22 July 1816. Their relationship was by several accounts not a happy one, with the Duke leaving her for long periods of time. After her husband’s death in the winter of 1834, the Duchess assumed the role of matriarch in the royal family. She became a confidante to the young Princess Victoria and posed with her, Prince Albert and their two eldest children for a daguerreotype in 1856. The longest-living and last-surviving child of George III, she died on 30 April 1857.

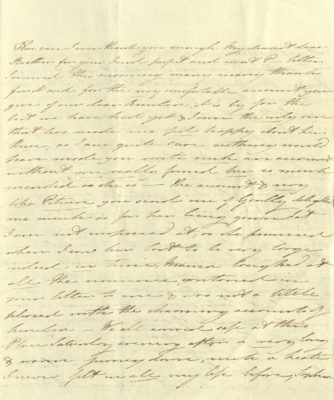

Princess Mary to the Prince of Wales from Weymouth, 1790. GEO/ADD/12/1/18 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Princess Mary’s correspondence, totalling just over 800 documents, consists of two smaller collections of different provenance, although both comprise letters to and from Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh, throughout her life. The first series in the collection mainly contains correspondence between Mary and her father, George III, and brother, George IV (as Prince of Wales, Prince Regent, and George IV). The documents range from Mary’s juvenile letters to her father dating from 1785 to a letter from Mary to Theresa Villiers, written possibly as little as a year before her death, in 1856. The second series of papers comprises letters received by Mrs Anna Maria Adams, neé Dacres, primarily from Princess Mary, but also from Mary’s elder sister, Princess Elizabeth, and other correspondents.

Mary was known to be one of the more sociable and amiable of the royal children and a favourite of some of her siblings. Always eager to mingle with society outside of Windsor Castle and Weymouth, her more youthful letters show her eagerness to attend balls and the theatre. More pressingly, her correspondence also expressed her need to escape Weymouth, which she described as “dull indeed, stupid and samey”, where “nothing does happen worth relating”. Mary clearly had a sense of humour, describing in one letter to the Prince of Wales from 1790, “George’s stupid old father” who looks like he “died three months ago and was taken out of his coffin to come & show he was alive to the King”. Mary’s willingness to involve herself in the outside world and converse freely with others, in particular her eldest brother, is the reason this correspondence is so rich. She clearly doted on the Prince of Wales deeply (she expresses her love for him both elegantly and at length in her letter of 7 October 1798), and provided him with information about their family, as well as treating him as a confidante.

While Mary’s life remained apparently scandal-free, she would relay details of the lives of her sisters to their eldest brother. She wrote to him of the “purple light of love” she saw in General Garth whilst at Weymouth with Sophia in 1798, and confided in him her belief that it was Amelia’s relationship with Fitzroy that killed her. Mary also came to hold a certain level of responsibility for her niece, Princess Charlotte, George’s only daughter, and it is she who reported to him on Charlotte’s wellbeing and movements in society. It is clear from Mary’s emotional reaction to her death in 1817 that she was deeply involved in Charlotte’s life. Mary also acted as a go-between for George and their family, for light-hearted matters such as conveying thanks for a pineapple sent to Queen Charlotte and the princesses, but also reporting on the health of George III and her suspicions that his mental breakdown was prompted by Amelia’s death, an opinion echoed in current theories on the matter.

Mary was Amelia’s closest ally during her life and also in death. Throughout Amelia’s illness and their spell at Weymouth, Mary frequently wrote to George III informing him of Amelia’s health, symptoms, treatments and improvements. The King encouraged Mary’s role as his primary source of information about his favourite child, writing to her: “I have taken care to make it understood that you are not to be separated from her”, implying that he regarded her as both a reliable correspondent, but also a good sister and companion to Amelia. Mary was also very tactical and adept in using her position with her elder brother to ensure that he behaved in a way which she believed was beneficial to their family and the Crown. For example, in the aftermath of Amelia’s death, she was very clear in instructing him how he must tell the royal family to act in order to minimise the scandal of Amelia having named Fitzroy as the primary beneficiary in her will, writing “I trust & hope no questions will be asked about it if any conversation should take place I am sure you will strongly recommend nothing more being said but that we were not ignorant that poor Amelia preferred him to all others” and that he should “for her sake be silent on Fitzroy”. Mary also organised aspects of Princess Amelia’s estate, informing her brother: “I likewise shall send you in a day or two a list of the charities Amelia used to distribute as of course you will give orders they should be paid up til next quarter & then make them understand they can continue no longer”.

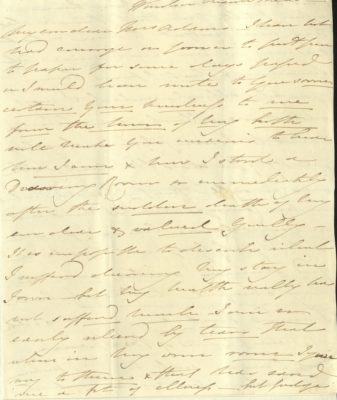

Princess Mary to Mrs Adams, 1804. GEO/ADD/12/2/12a Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

While Mary was clearly hugely important within her family, it is evident she built and maintained strong relationships with the women who cared for her, educated her and chaperoned her in her youth and childhood. Her correspondence with Mrs Adams, her old wet-nurse, alone is proof of this. Adams (c. 1752-1830), was the daughter of Richard Dacres, one-time secretary to the garrison at Gibraltar and sister of Rear-Admiral James Richard Dacres. Anna Maria married William Adams in 1774, who went on to have a successful political career. Her sister, Mary Dacres, had been the beloved ‘dresser’ of the Princess Royal and Princess Augusta, and Anna Maria was brought in as Princess Mary’s wet-nurse for the first eighteen months of her life. Some sources suggest that she also acted as wet-nurse for Princess Amelia, and then as lady-in-waiting to Princess Mary, which would explain why they maintained such an extended and detailed correspondence throughout their lives. Mary kept Mrs Adams informed of Amelia’s illness and George III’s mental health, as well as the everyday and scandalous goings-ons of the royal family. The two women also maintained a relationship with Miss Martha “Goully” Goulsworthy, former sub-governess and chaperone to the princesses, whom Mary described as a “dear and valued servant”. Mary reacted emotionally to Goully’s death, who had left a letter for the princesses, and a little money.

Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh c. 1856 Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

However, Princess Mary’s interests did not solely cover the domestic sphere. Many of her letters show an interest in and knowledge of the outside world. For example, she congratulated the Prince of Wales on “Nelson’s Glorious Victory” and informed Mrs Adams of the Braganzas’ flight to Brazil in 1807. Mary was also, as shown in her handling of the aftermath of Amelia’s death, very aware of the political implications of the family’s seemingly domestic or familial decisions. She warned the Prince Regent, concerning plans for the care of Princess Charlotte “that if it was proposed in a Political point of view the sooner it took place the better”.

Princess Mary is arguably not one of the most well-known figures in Georgian history, and her position as a woman, particularly as a daughter of Queen Charlotte, meant that she was not allowed a huge amount of agency within the wider world. However, her actions and observations within the spheres in which she operated are fascinating, informative and on occasion very entertaining, and provide an insight into female relationships, familial dynamics, and social mores in the Georgian era, as well as a more personal and subjective view of subjects such as George III’s health and her brother George’s Regency and succession to the throne.