Thomas Gainsborough, Queen Charlotte, 1782 ©

Often in the shadow of her more famous husband, George III, and son, George IV, Queen Charlotte is a figure that is often overlooked. The papers stored in the Royal Archives – and now available online – give us chance to get to know the life of this dutiful wife, mother and queen.

Letters to a husband and king

Born in Mirow, a small town in north-eastern Germany, Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz had little inkling that she would one day be Queen of Great Britain and Ireland. Yet as a protestant with a good character, Charlotte was one of the only eligible options for a bride to the new King of England. George and Charlotte did not meet until their wedding day (8 September 1761), and any correspondence that may have existed prior to their marriage is not in this collection. A delegation headed by the Earl of Harcourt was dispatched to escort the new bride to England, a journey which is described in detail by one of the party, Hugh Hughes, in his journal.

Compared to many of their contemporaries the marriage of George and Charlotte was very successful not only as their numerous offspring (15 in total) attest but also in the esteem that Charlotte held her new king. Writing on 26 April 1778, nearly 17 years after their marriage, Charlotte’s affection for George is clear; as she concludes her letter to him:

You will have the benefit by Your voyages to put Spirit in every Body, to be more known by the World, and if Possible more beloved by the People in general. That must be the case, but not equal to the love of her who subscribes herself Your very affectionate Friend and Wife Charlotte

Queen Charlotte to King George, GEO/MAIN/36352-36354

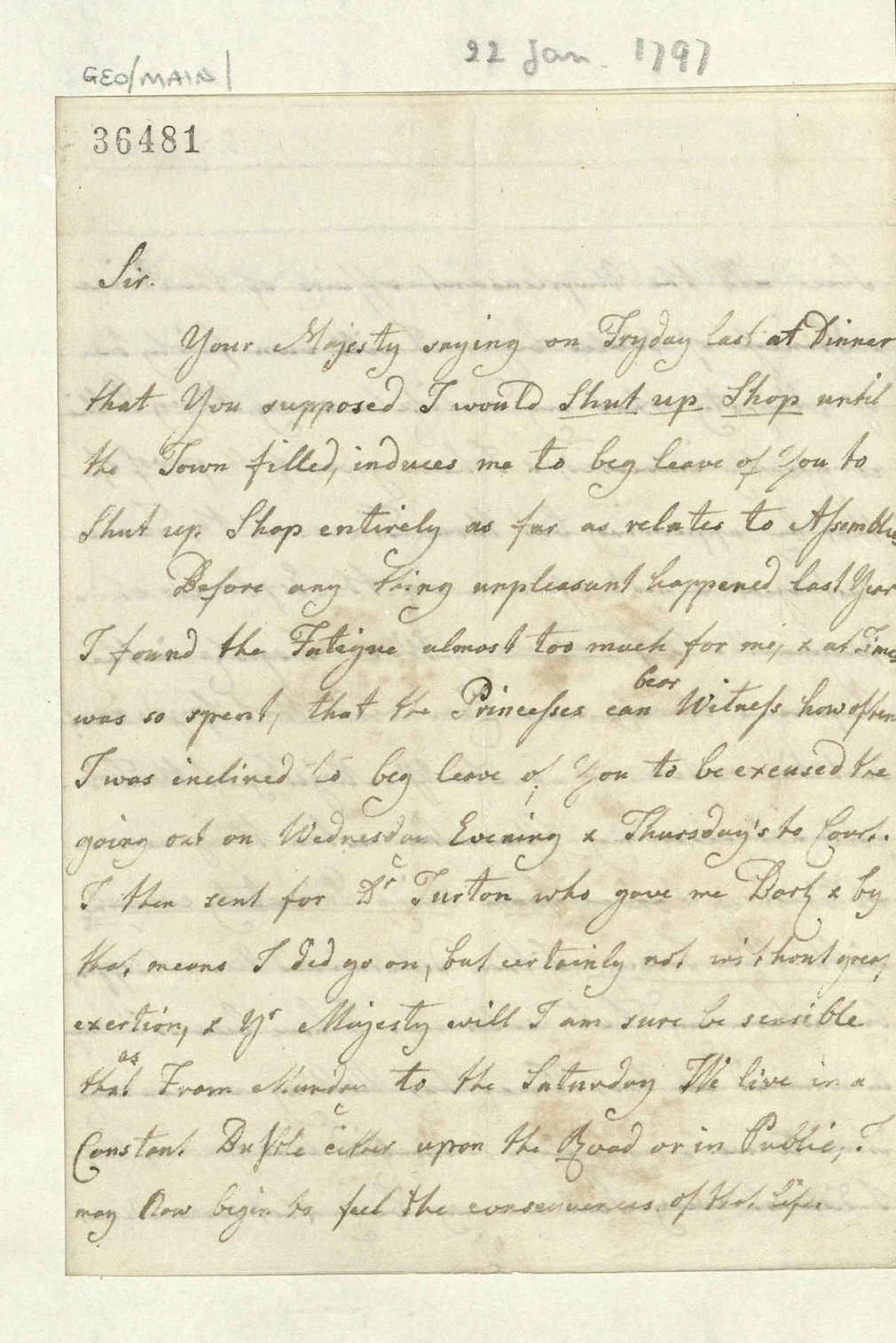

Letter from Queen Charlotte to George III, 22 January 1797, GEO/MAIN/36481-2 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Only a handful of Charlotte’s letters to George III survive among the Georgian Papers and it is questionable how many ever existed as the king and queen were so frequently together. However, even in these fragments we can still glimpse a change in their relationship. Worn down by the fatigues of court life and strained by worries over her husband’s health and the turbulent love life of her beloved eldest son George, Charlotte’s nature changes. Despite her devotion to fulfilling George III’s commands, she pleads a release from her attendance at court:

As Yr Majesty at the Time could not clear my Character when things were at the worst in London, from being Privately connected with Ldy Jersey [lover of the Prince of Wales]. I then determined never to appear but where my Duty called me. I have been so thoroughly wounded at that Time, that nothing ever can make it up to me & my dislike to Mankind is so general, that I distrust every Soul & every body that surrounds me & I trust that my Sincerity in telling Yr Majesty the Truth will lead You to acquiesce in my request

Queen Charlotte to George III, 22 January 1797, GEO/MAIN/36481-36482

George III and Charlotte were never to regain their former closeness and attachment.

Queen Charlotte with her two Eldest Sons, c.1764-9, RCIN 404922 ©

Letters to George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent

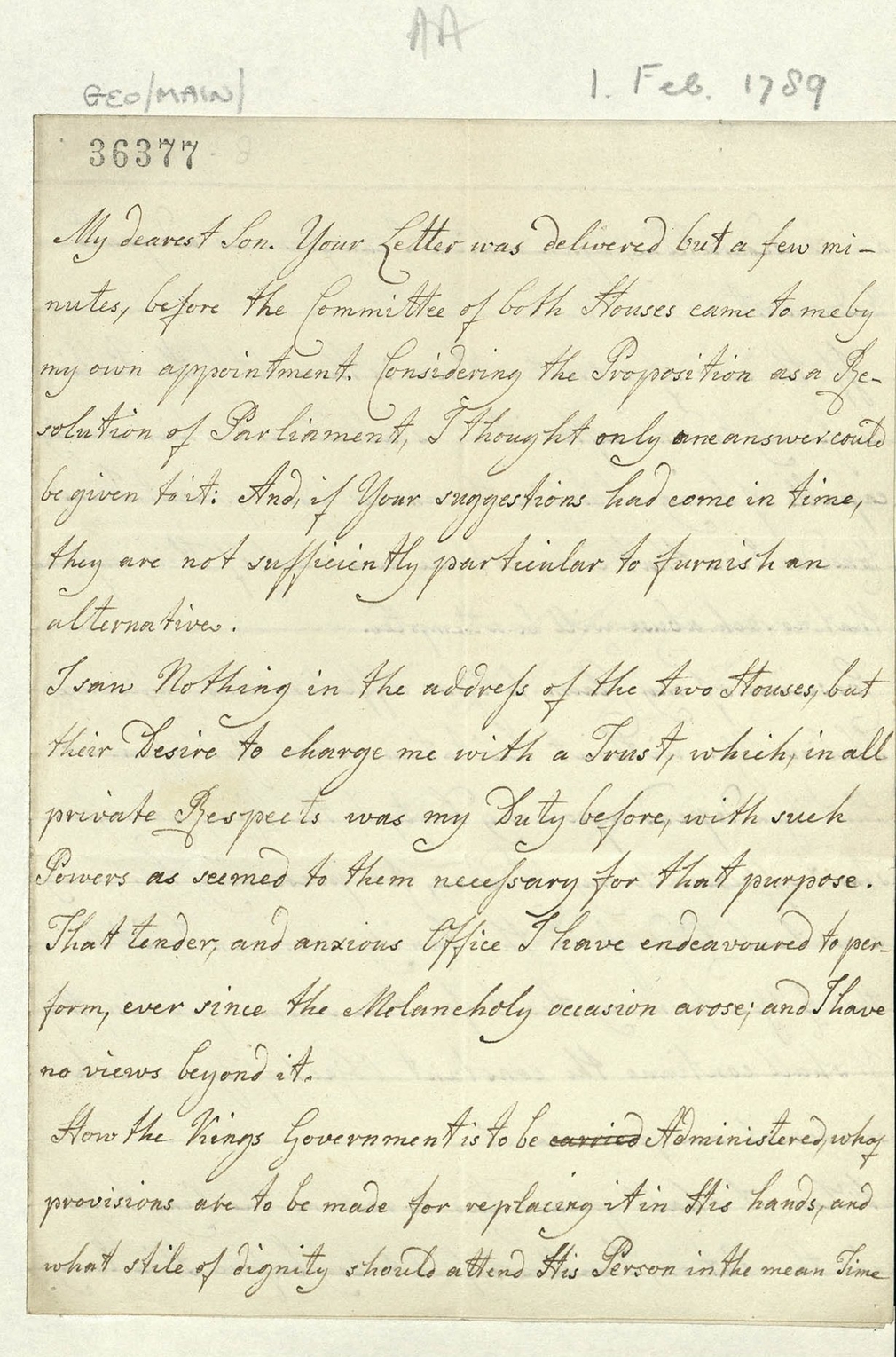

Whereas only about a dozen letters from Queen Charlotte to George III survive in this collection, over 300 letters held in the Royal Archives are written by Queen Charlotte to her eldest – and most likely favourite child – George, Prince of Wales, later Prince Regent. (Charlotte was not to see either of her sons become king as she predeceased her husband George III in 1818). These cover a range of subjects from motherly advice, updates on other family members, birthday wishes, his daughter Princess Charlotte and general comments on current affairs. The letters also highlight Charlotte’s role as a mediator between her husband and her son but the first major bout of illness suffered by George III in 1788-9 undoubtedly placed a strain on the relationship between mother and son.

While the Prince of Wales wished to assume greater powers during the illness of his father, he failed to gain his mother’s support. On 1 February Queen Charlotte wrote:

How the Kings Government is to be […] administered, who provisions are to be made for replacing it in His hands, and what stile of dignity should attend His Person in the mean Time are considerations, upon which I can form no adequate Judgement.

This saw the beginning of a serious rift between mother and son with Charlotte writing pointedly several days later:

I have only to add that it was not owing to Lady Harcourt’s presence that I said nothing particular to You & Your Brother, but that I had Nothing to Say. which Confession must surprize You as it come[s] from a Woman.

Unlike her relationship with her husband, Charlotte’s relationship with her son survived the breach and following the Prince’s estrangement from his wife Caroline of Brunswick, Charlotte presided over the royal court during the Regency in her stead.

Queen Charlotte’s letter to George, Prince of Wales, 1 February 1789, GEO/MAIN/36377 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Although Queen Charlotte had no active role in politics – notably resenting and resisting attempts to bring her into formal decision-making during the illness of the king in 1789 – that is not to say that she had no official part to play. Copies of her letters and correspondence with foreign nobility (typically European royalty) still exist in the archive in series GEO/ADD/41. Most of these letters are formulaic – congratulations on births and marriages, letters of condolence on deaths, best wishes for the coming year – but they remind us to put the British monarchy in the European context (not least because the majority are written in French!) and that Queen Charlotte had originally been a European princess and is herself part of this wider European context.

Financial papers

Despite having none of the spendthrift ways of her son, the future George IV, like him, Queen Charlotte ran into debt. In a letter of 15 April 1796 to George III, Charlotte explains her financial circumstances and the inadequacy of the allowances in clothing the younger princesses and providing pensions for retired members of staff. But in essence, ‘the Fact is that the Expenditure greatly exceeds every Quarter the means of paying it’ writes her Treasurer Lord Ailesbury.

The collection of financial records provide us with detailed breakdowns of Queen Charlotte’s accounts including payments to members of her household. Further lists of staff for the start and end of Queen Charlotte’s reign have also been digitised (EB/EB/43 and GEO/ADD/24). In terms of personal expenditure, only two account books survive for 1789 and 1806 (GEO/ADD/2/66 and GEO/ADD/2/67 respectively). But we can see evidence of Queen Charlotte’s charitable donations e.g. payment of £3 3s to ‘a poor Hannoverian Soldier’ and the same amount to a blind man both on 26 August 1789.

Personal papers

Queen Charlotte was a woman committed to a strong sense of duty and firm faith. Clever and widely read, Charlotte copied out a number of published texts on religious and moral works for her personal reflection. Queen Charlotte’s notebooks in ADD43 are, like George III’s essays, personal copies of published texts and reflect a wide range of reading and an interest in history, literature, and morality. With a deep personal commitment to learning and her interest in children’s education, Queen Charlotte also devised a set of ‘flashcards’ on European history presumably for use in a game. Manuscript cards for the history of the German Empire and for Portugal can be found among these papers while a more complete printed set is held by the Royal Library (RCINs 1128953–1128957) due to be digitised later this year.

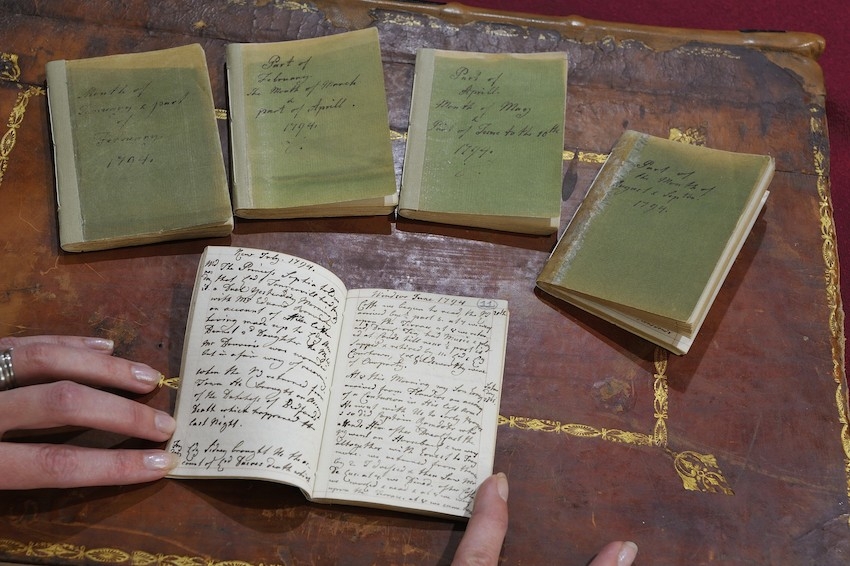

Most personal in this collection is the series of Queen Charlotte’s diaries for 1789 and 1794. It is not known whether Queen Charlotte kept diaries only for these years or whether the ravages of time have meant that only diaries for these years have survived. The diaries for 1789 unfortunately begin only in August part way through the trip to Weymouth undertaken for the benefit of the King’s health – and indeed only a few months after his recovery from his first serious bout of ‘madness’ in February 1789. The ‘holiday diary’ of life at Weymouth for August and September provides an interesting counterpoint to the usual routine of life in Windsor and court life in London as seen in the diary for October – December 1789.

Queen Charlotte’s diaries Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Although these diaries tend to be a factual account of Queen Charlotte’s daily activities rather than a record of her thoughts and feelings, they do provide us with greater context to the life of the Royal Family. The constant travelling between the Windsor and London or Kew residences in particular – and the disruption it causes – is clearly illustrated. As the diary for February to April 1794 illustrates, the King and Queen in particular split their time between Windsor and London and frequently undertook this journey, for example, London, 18–21 February; Windsor, 22–24 February; London, 25–28 February; Windsor, 1–3 March; London, 4–10 March; Windsor, 11–12 March; London, 13–17 March; Windsor, 18–19 March; London, 20–24 March. Whereas we could now expect this journey to take roughly an hour, in the Georgian period this would have taken around 2–2.5 hours – given the state of the roads and the construction of the carriages, this is unlikely to have been a comfortable journey!

When reading about the lives of historical figures, it is sometimes easy to forget that they, like us, had their share of physical discomforts, boredom, sorrow, friendship, and love. The gift by Queen Charlotte of her own hair to her friend Mrs Delaney reminds us of her feelings even when they may be obscured by gaps in the historical record.