8. History cards

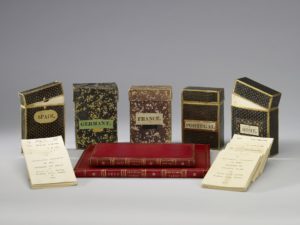

GEO/ADD/43/20/1-2: ‘German Empire’: Manuscript of published text written on individual cards by Charlotte, Queen Consort of George III [1810]: the finished item RCIN 112854 in the possession of the Royal Collection Trust

Windsor : E Harding, A Chronological abridgement of the history of Germany (Frogmore. 1810) Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 1128954, (c) Her Majesty the Queen. Click on the image to see in higher resolution.

Click on image to see the full set and read in high definition; click here to read the Royal Archives catalogue entry

Queen Charlotte’s interest in history, literature and the arts extended, as did her husband’s, to the material aspects of learning. The establishment of a printing press at Frogmore House in 1809, her retreat on the grounds of Windsor Castle, is one important example. There, her librarian and printer Edward Harding helped to create printed versions of some of the Queen’s (and some other writers’) work. Only a small edition of each publication was issued from the Frogmore Press, usually intended for private use and as special gifts.

These extraordinary history cards, printed at Frogmore House and then housed in boxes possibly created with the assistance of the royal bindery at Windsor, reflect and drew on the historical narratives that Queen Charlotte and other women at court, including her daughters, were reading and writing. They were described as ‘Chronological Abridgements’ and five sets were created for the history of Spain, Germany, France, Portugal, and Rome. (We know that at least one further set of each is now held at the British Museum.)

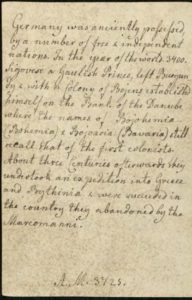

The box containing the manuscript cards

There are two related set of objects, the manuscript (handwritten) version of the cards, and then the printed sets. A full set of manuscript cards exists only for two of the printed sets. Seen here is one of the manuscript cards for the German Empire, with the accompanying box. Surely there would have been earlier, rougher drafts, and it is likely that we could match up some of the Queen’s narrative histories with the contents of the cards.

What was the purpose of these cards? They have been described and catalogued elsewhere as ‘playing cards’, but given that the Queen intended to gift them to young people it is more likely they were designed for instruction. In the late eighteenth century other such cards, of the sovereigns of England, for example, were popular enough to justify the costs to commercial printers of making and marketing them.

[Queen Charlotte’s curriculum cards were also included in another Georgian Papers Programme online exhibit, the Audience for Hamilton’s George III, Michael Jibson.]

9. Lady Augusta Murray’s Commonplace Books

GEO/ADD/51: Lady Augusta Murray’s commonplace books and book of cures c.1778-1812

After Robert Fagan, The Lady Augusta Murray. Work on paper, 23.0 x 18.3 cm. Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 604932

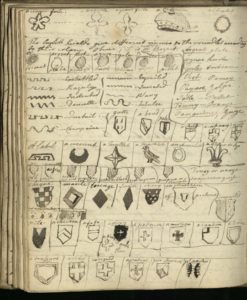

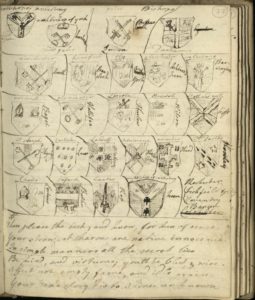

Pages in Lady Augusta Murray’s commonplace book c. 1789 (GEO/ADD/51/1), fos. 76v-77r, showing heraldic sketches. Click on the images to see the whole commonplace book in high resolution. Click here to see the Royal Archives Catalogue entry.

Lady Augusta Murray was the wife of Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, the sixth son of George III. Following their marriage at the Hotel Sarmiento on 4 April 1793, which took place without witnesses and without asking the permission of the King, the union was deemed illegitimate in accordance with the Marriage Act of 1772 and, from 1801, the couple lived separately. Several of Murray’s commonplace books, dating from 1785 until 1810, survive at the Royal Archives as important records of her intellectual and emotional life. Commonplacing offered women a manuscript space in which to collect anecdotes, recipes, proverbs, songs and poems and to demonstrate their knowledge of history and travel. Extracts by a range of authors, including those in Murray’s circle at court, were gathered together by Murray as visual and textual curiosities that could be shared, displayed, and used to reflect her own identity. Across her four surviving commonplace books, Murray’s interest in history, art history and antiquarianism are vividly represented in the fabric and content she preserved.

Lady Augusta Murray was the wife of Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, the sixth son of George III. Following their marriage at the Hotel Sarmiento on 4 April 1793, which took place without witnesses and without asking the permission of the King, the union was deemed illegitimate in accordance with the Marriage Act of 1772 and, from 1801, the couple lived separately. Several of Murray’s commonplace books, dating from 1785 until 1810, survive at the Royal Archives as important records of her intellectual and emotional life. Commonplacing offered women a manuscript space in which to collect anecdotes, recipes, proverbs, songs and poems and to demonstrate their knowledge of history and travel. Extracts by a range of authors, including those in Murray’s circle at court, were gathered together by Murray as visual and textual curiosities that could be shared, displayed, and used to reflect her own identity. Across her four surviving commonplace books, Murray’s interest in history, art history and antiquarianism are vividly represented in the fabric and content she preserved.

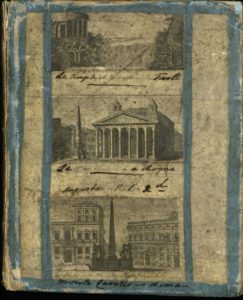

The front board of GEO/ADD/51/1.

In a volume from 1789 [GEO/ADD/51/1], for example, the front and back boards are decorated with hand-cut and pasted engravings of Italian monuments that would have been familiar to any traveller on the Grand Tour. Although some women did travel in this way, the Grand Tour was more usually the preserve of young aristocratic men. Murray’s collection of visual representations of these sites is perhaps her way of signalling knowledge of locations and buildings considered important in broader antiquarian conversations and established art history. The images, which include the Temple at Tivoli, the Parthenon and the Palazzo del Quirinale at Monte Cavallo in Rome, also lend antiquarian authority to Murray’s commonplace book and work to introduce further historical content inside.

Inside her commonplace books, Murray demonstrates a keen interest in the history of Europe and, in particular, of its royal courts. British history, with its cast of historic kings, queens, and nobles, was regularly reconfigured in order to construct patriotic narratives and affirm Hanoverian dynasty at the royal court and beyond. Among extracts from poems and essays she gathered from various printed sources are lists of monarchs and genealogical notes spanning periods of British, French and Spanish royal histories. Her 1789 volume includes a ‘List of Kings and Queens of England, starting with William the Conqueror’ [GEO/ADD/51 fo. 115r] alongside a ‘Genealogical description beginning with King Louis XIV [fo. 43v]. Murray is similarly fixated on classical history, an interest already established via the printed and watercolour images pasted onto the boards of several of the commonplace books. In the same volume, she writes out a lengthy entry covering ‘A history of ancient Rome, beginning with its foundation by Romulus, and containing a chronological list of Roman Emperors with a description of their character’ [fo. 73r]. Written in French, this entry demonstrates the breadth of Murray’s classical and linguistic education.

Murray’s commonplacing was not merely an exercise in copying-out established historical and poetic texts from the period. Instead, it is likely that Murray’s notes were used as prompts deployable in conversation, allowing her to record and recall historical information and demonstrate her authority as a historian. Among her writings are ‘Notes on the attitude of various historians to the reputation of Richard III’ [fo. 82v] and ‘several historians’ assessments of the character of Charles II’ [fo. 95v], revealing Murray to be a wide and critical reader constantly reviewing the historical literature.

Murray also includes two pages [fo. 76v – fo. 77r] covered in sketches of heraldic symbols accompanied by labels detailing the meanings of various components. Useful as a catalogue of visual and textual information, Murray’s heraldic pages show her interest in collecting this kind of historic data alongside poems, maxims and other commonplace content. Her interest in the encoded meanings of heraldic symbols is also in line with the work of prominent eighteenth-century antiquarians including Horace Walpole, who was an avid collector of medieval heraldry. Here, Murray makes interesting and economic use of the manuscript page. She deconstructs the complexities of the coat of arms, isolating individual visual motifs which she organizes in a table of her own design. Symbols including a crescent, an amulet and a fleur de lys are separated into individual boxes, reminiscent perhaps of the collector’s cabinet. On the second page of the heraldic material, Murray records the details of coats of arms of different bishoprics including those of Oxford, London and York.

10. A Découpage album by Mary Delany

GEO/ADD/2/65: Book of découpage by Mrs Mary Delany. Given to Queen Charlotte by Mary Delany, 13 November 1781.

John Opie, Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany, 1782. Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 63.6 cm. The Royal Collection Trust: RCIN 400965. This portrait was commissioned from Opie by George III and hung in the bedchamber of her friend and benefactor Queen Charlotte at Buckingham House.

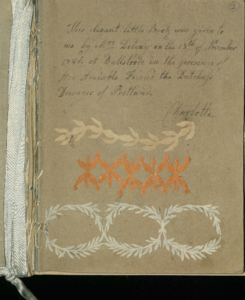

Page numbered 1, with an inscription inside the album by Queen Charlotte records how the work was gifted to her by Mary Delany during a royal visit to the Duchess of Portland’s estate Bulstrode Park in 1781. Click on the image to see the whole of the book in high definition; click here for the Royal Archives catalogue entry.

This album of découpage was made by the artist and Bluestocking Mary Delany (1700-88) and gifted to Queen Charlotte in 1781. Previously unknown to scholars, this important object was the subject of an article by GPP fellow Madeleine Pelling and published in Journal 18. It covers twenty pages forming blue grounds and contains 114 individual paper cut designs, from intricate and realistic botanical representations to more abstract decorative motifs. Mary Delany, born Mary Granville in Ireland in 1700, is known today for her famous botanical paper mosaics – cut and coloured paper arranged on black grounds to resemble botanical specimens taken from a number of elite sites including Kew Gardens, Kenwood House and Bulstrode Park. Throughout her life Delany was a regular visitor to Bulstrode, home to her close friend the widowed Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, 2nd Duchess of Portland (1715-85). George III and Queen Charlotte were regular guests of the duchess whose famous collection of art works, antiquities and natural-history specimens became known as the Portland Museum. In 1781, Charlotte visited Bulstrode, where Delany presented the queen with her paper-cut album. Writing in a letter the next day, Delany described the scene:

The Duchess of Portland returned home in order to be ready to receive the Queen, who immediately followed, before wee [sic] could pull of [sic] our cloaks! We receiv’d her Majesty and the Princesses on the steps at the door, but she is so gracious that she makes everything perfectly easy. We got home a quarter before eleven, and the Queen staid till two.

As well as symbolizing the friendship between Delany and the queen, the album may have acted as a visual record of the museum, its objects and themes. Charlotte was particularly involved in the duchess’s museum and contributed flowers to its natural-history holdings as well as borrowing books from the library. Here, the album acts as an extension of the cabinet space, representing the types of objects in the museum in a new visual and material medium.

Paper cutting such as this was part of a wider tradition of craft work engaged by women at the royal court and beyond. The queen and her daughters all worked with cut paper, embroidering, spinning and drawing, activities that can be read about on the GPP blog here. In Delany’s album, cuts are generally grouped according to theme; there are whole pages of botanical designs, classical figures and decorative patterns. Red paper, for example, is cut to represent classical urns and vases reminiscent of the fashionable taste for the ancient world characterized in aspects of the collection at Bulstrode. Different shades of green papers are cut with minute accuracy to represent various types of flowers and plants. Elsewhere in the album, thick cream coloured paper is used in the silhouette cuts of people. There are three silhouette portraits including one of George III, with the other two copied from busts possibly also representing the king or his sons.

END OF EXHIBITION

Further Reading

We have included a bibliography as a starting point, and to indicate some of the work we used in preparation of this exhibit, though it is by no means exhaustive.

As research in the Georgian Papers continues, new information and new interpretations will develop. We look forward to seeing how this informs what we have written here about history at Queen Charlotte’s court, and how it will intersect with the work of other scholars investigating women and historical thinking in the eighteenth-century Anglo-Atlantic world.

_______

Fraser, Flora. Princesses: The Six Daughters of George III. London: John Murray Publishers, 2004.

Hall, Augusta, Lady Llandover (ed.). The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany: With Interesting Reminiscences of King George the Third and Queen Charlotte. 6 vols in 2 series. London: Richard Bentley, 1861-2.

Hodgkin, Kate. ‘Women, Memory, and Family History in Seventeenth-Century History’, in Erika Kuijpers et al. (eds). Memory Before Modernity: Practices of Memory in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2013, 297-313.

Laird, Mark, and Alice Weisberg-Roberts. Mrs Delany and Her Circle. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Malay, J. L. The Anne Clifford Project. https://research.hud.ac.uk/institutes-centres/anneclifford/

Marschner, Joanna, with David Bindman and Lisa L. Ford (eds). Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Mycock, Jane. The Commonplace Books of Lady Augusta Murray. Royal Collections Trust Online. https://www.rct.uk/collection/georgian-papers-programme/the-commonplace-books-of-lady-augusta-murray

Roberts, Jane (ed.). George III and Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2004.

Roberts, Jane. ‘Edward Harding and Queen Charlotte’, in Danian Derthloff et al. (eds), Burning Bright: Essays in Honor of David Bindman. London: UCL Press, 2015, 146-59.

Tobin, Beth Fowkes. The Duchess’s Shells: Natural History Collecting in the Age of Cook’s Voyages. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Vallone, Lynne. ‘History Girls: Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Historiography and the Case of Mary, Queen of Scots’, Children’s Literature, 36 (2008): 1-23.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

Curators and text: Madeleine Pelling and Karin Wulf

Mounting of Exhibition: Arthur Burns, Sara Belmont

Transcriptions: Georgian Papers Programme, with contributions by Claudia Ardevines Puyuelo, Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf.

Liaison with Royal Archives and Royal Collection Trust: Oliver Walton

The exhibition organizers also wish to thank Claudia Ardevines Puyuelo for permission to draw on her digital edition of Queen Charlotte’s notes on Charlemagne completed as part of her assessment for the undergraduate module ‘At the Court of King George: Exploring the Royal Archives’ at King’s College London.

Unless otherwise specified, all images in this exhibition are suppplied by the Royal Archives and are © Her Majesty the Queen 2016-19.