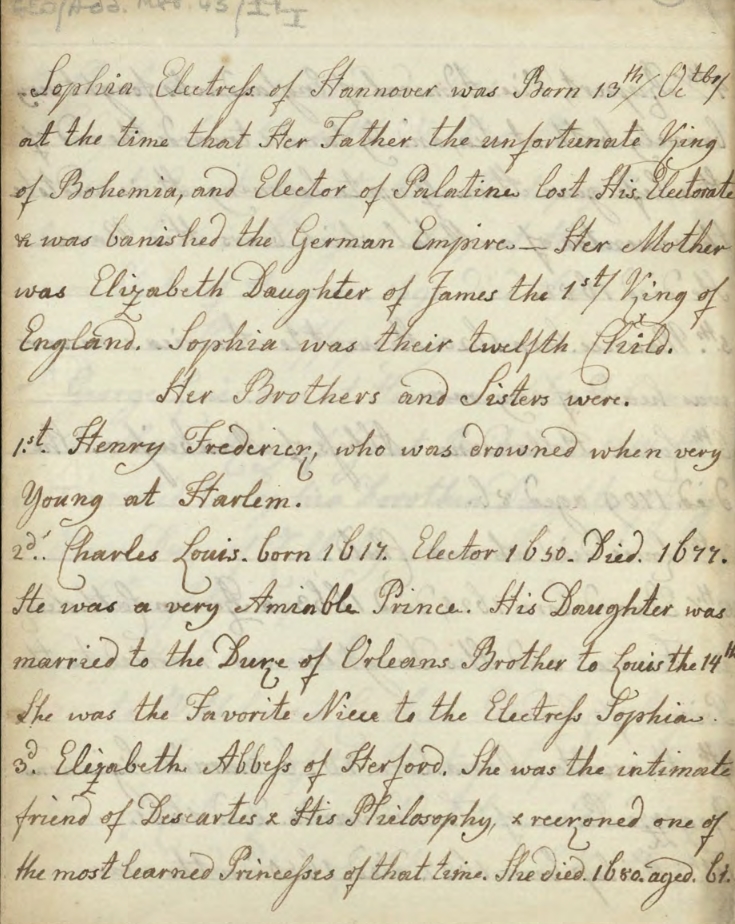

1. Sophia, Electress of Hanover

Jean Michelin, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, c. 1670. Watercolour on vellum laid on card, 7.0 x 5.5 cm The Royal Collection Trust: RCIN 420627. The Trust notes that this miniature ‘features among a group of eighty-eight representing German and other families first recorded in Queen Caroline’s Closet at Kensington Palace in 1743’.

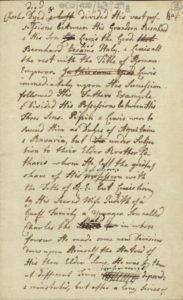

GEO/ADD 43/19i: Notes on the life of Sophia, Electress of Hannover, by Charlotte, Queen Consort to George III (n.d., 1761-1818).

Queen Charlotte wrote out at least these three copies of the lines of descent in the British royal family beginning with Sophia, the Electress of Hanover.

Click on image to read in full and high definition. To read the Royal Archives Catalogue entry, click here. For a full transcription, click here.

(Queen Charlotte’s notes about Sophia were also included in an another Georgian Papers Programme online exhibit, ‘An Audience for Hamilton’s George III, Michael Jibson’.)

Queen Charlotte’s interest in Sophia of Hanover was likely at least twofold. First, Sophia was the crucial link in the negotiated succession that eventually brought Charlotte’s husband to the throne. As part of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the royal succession skipped the catholic heirs of James II, installing instead his Protesant daughter, Mary, and her husband, William. With William and Mary not having children of their own, the crown then went to Mary’s sister, Anne, also a Protestant and after Anne to George I, the great grandson of James I through his mother, Sophia of Hanover. George III was the third of the Hanoverian kings.

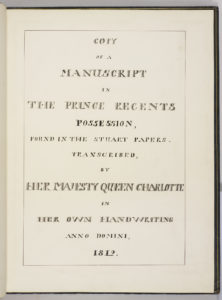

Titlepage of Charlotte’s transcription of Stuart documents: Royal Collection Trust RCIN 1046711.

The lineage Queen Charlotte copied and re-copied emphasized the importance of that connection of Sophia to the Hanoverians. Queen Charlotte was well aware of the complexities of the English royal succession, and how the (Catholic) Stuarts had been bypassed in favour of Sophia’s (Protestant) line. Among other that the Queen was working with were some Stuart manuscripts that included a poignant letter from the exiled James II to his son, who would never be king.

Second, Queen Charlotte was likely interested in Sophia’s circle of learned women. Her notes specify important historical and genealogical information about births (including birth order), marriages and deaths, but the queen also included details that illustrated the interests and virtues of the women in the royal family’s history. She noted the intellectual pursuits of two women in this lineage in particular: Elizabeth the Abbess of Hertford, ‘the Intimate Friend of Descartes & His Phy-losophy & reckoned one of the most learned Princesses of that time’ and ‘Willhelmina Caroline Princess of Anspach a great Favorite of the Electress Sophia & a Scholar of Leibnitz’. The latter was Queen Caroline, George III’s grandmother whose guardian as a girl was Sophia Charlotte, Sophia’s daughter. Sophia and Sophia Charlotte helped to cultivate court environments in Germany in which women’s intellectual abilities and pursuits were encouraged. Thus, Queen Charlotte’s interest in the lineage of Sophia, Electress of Hanover may have been as much about the legacy of women’s intellectual lives and activities as it was about the Hanoverian succession in Britain.

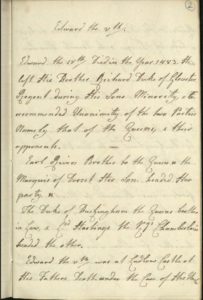

2. Queen Charlotte’s Essays on the History of England from Edward V to Henry VII

GEO/ADD/43/7: Essays on the history of the English monarchy from Edward V to Henry VII by Charlotte, Queen Consort of George III (26 November 1792)

Click on the image to see the full set of essays in high definition. To read the Royal Archives’ catalogue entry, click here. For a transcript, click here.

‘Windsor the 26th of November, 1792.’ In 1792 Queen Charlotte had just reconciled with her son, the Prince of Wales, her husband seemed to be recovered from a severe bout of the mental illness that plagued him in the late 1780s, she was planning her house and gardens at Frogmore House, and she was worrying about the intensifying events of the French Revolution and planning to offer refuge to the French royal family. She was also at work on copying out the history of England.

This manuscript volume begins with the death of Edward IV in 1483, and a period of English history that had gripped the nation’s imagination since. The reign of Richard III, the fate of the fabled ‘Princes in the Tower’, and the beginning of the Tudor era all came together in this period.

Queen Charlotte’s writing seems to emphasize the role of women in this tumultuous period. In the wake of Edward IV’s death, before the death of his sons and the ascension of Richard, it was the queen, the former Elizabeth Woodville, and her relatives who were at the forefront of the story. This manuscript is one in which Queen Charlotte was copying quickly, or at the very least was not reluctant to make substantial deletions and corrections. In the first pages, the section she was crossing out and rephrasing was the episode in which there were accusations against ‘the Dowager Queen, and Jane Shore the late king’s Mistress of plotting against his life’. Though they were found innocent, Jane Shore ‘was acquitted & ended her Life in great Indigence’.

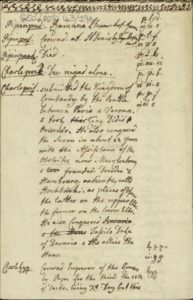

3. Notes on the reigns of Pippin and Charlemagne

GEO/ADD/43/19a: Notes on the reigns of Pippin and Charlemagne by Charlotte, Queen Consort of George III [n.d., bet. 1761 and 1818]

Queen Charlotte’s Notes on the Reigns of Pippin and Charlemagne, complete with her code for representing dates of historical events. To see the whole document in high definition, click on the image; for the Royal Archives Catalogue Entry, click here; for a transcription, click here.

Queen Charlotte was greatly interested in models of royal rule in the past. This short and informal piece of writing was composed by Charlotte to her husband George III, and documents the reigns of Pepin the Short, King of the Franks (c. 714– 68) and his son Charlemagne, King of the Lombards and later Emperor of the Romans (742-814). Charlotte, who had been born in Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a north-German duchy in the Holy Roman Empire, was captivated by European histories. Her interest in Charlemagne might also be understood as a symptom of a wider interest in this enigmatic historical figure. Throughout the eighteenth century, Charlemagne was adopted by various political figures, including Napoleon Bonaparte, as a champion of European, particularly French, power.

Charlotte’s account of Charlemagne’s life is full of precise details and includes dates, names, and places, demonstrating the extent and accuracy of her historical knowledge. Marginal labels on the left of the page function like tags, indicating which king Charlotte is writing about and working, perhaps, as a finding aid so that a reader might locate and reuse the information written by the queen for later use. Pen trials at the top of the first page, coupled with crossings out throughout the main body of the text, confirm that this is not a formal document. Rather, Charlotte has created a useful tool that might be brought out and used in later reference, one exchanged between the queen and her husband as part of a broader culture of historical discourse within the royal court.

Along the right-hand side of Charlotte’s text are seemingly random letters, usually grouped in threes and often crossed through. While an undergraduate student studying this document at King’s College London, Claudia Ardevines Puyuelo identified these features as a code used, and possibly created, by Charlotte to record the dates of major historical events such as the crowning and deaths of monarchs. Here, vowels are assigned a numerical value that, when combined on the page, represent particular dates (the code is explained in detail in the transcription document). Codes such as these were popular throughout the eighteenth century and show the queen’s interest in recording and representing history in increasingly creative and intellectually complex modes. It is unlikely that Charlotte used this code in order to keep particular information secret and inaccessible to potential readers of her notes. Rather, these abbreviated records might have been useful in storing and recalling historical data in later conversations and textual composition.

4. Notes on the History of the Franks from Charlemagne to Charles the Fat

GEO/ADD/43/19b: Notes on the history of the Franks from Charlemagne to Charles the Fat by Charlotte, Queen Consort of George III [n.d., between 1761 and 1818]

To see the whole document in high definition, click on the image. To read the Royal Archives catalogue entry, click here. For a transcript, click here.

Queen Charlotte’s interest in Charlemagne and the politics of medieval Europe continues in this draft of an essay on the history of the Franks. In it, Charlotte examines the division of what is now France and Germany under the rule of Charles the Bald, king of West Francia, Italy, and eventually the Carolingian Empire (823-77).

The queen is particularly interested in national histories, and the claims eighteenth-century historians made for Charlemagne and his successors as the heroic originators of different, sometimes opposing, European countries. Far from a simplistic retelling of established historical narrative, Charlotte’s essay signals her interest in contemporary historiography, and demonstrates both her knowledge of current historical debate and its political implications. She writes:

‘Hence arises this Question so Interesting to the German History. Whether or not this Prince as the only remains of this Race could make any pretentions to the German Empire? As it is from thence that many Modern Authors Suppose the Crown of France to have some pretentions to Germany.’

It is known that Charlotte, whose first language was German, was self-conscious about the many mistakes she made when writing in English. Across this document are instances of another hand used to correct some of her misspellings. For example, at the top of the first page, this anonymous editor has underlined Charlotte’s ‘Dyed’ in a dark black ink and written the correct ‘Died’ above, revealing something of how essays like this might have been shared, edited, and perhaps even co-authored at court.

5. Extracts from the diary of Lady Anne Clifford

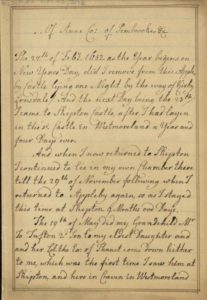

GEO/ADD/43/19k: Extracts from the diary of Lady Anne Clifford, Countess Dowager of Dorset, Pembroke and Montgomery, by Charlotte, Queen Consort of George III (n.d. between 1761 and 1818)

William Larkin, Anne, Countess of Pembroke (Lady Anne Clifford), c.1618. Oil on panel, 22 5/8 in. x 17 1/8 inches. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Only four tantalizing pages survive here of Queen Charlotte’s transcription of the diaries of Lady Anne Clifford (1590-1676). Copying out sections from either manuscript or printed sources — ‘commonplacing’ — was widely practised. It helped the transcriber to reflect on, to remember, and also to preserve key texts that were meaningful. A question for us is in what ways particular texts were meaningful to the transcriber, in this case Queen Charlotte, and why.

To read the whole document in high definition, click on the image. For the catalogue entry in the Royal Archives, click here. For a transcript, click here.

Lady Anne was an extraordinary character who, like other powerful women in England’s history, clearly captured the Queen’s attention. She was the daughter of the third Earl of Cumberland who, when he died without a son, tried to leave his property to his brother. Anne famously battled in the courts for and won the inheritance of her family lands and title. Among her extensive holdings she owned the castles at Skipton, Appleby and Brougham.

Lady Anne was creative and lavish in commissioning art, building works and more. She employed secretaries and librarians to help keep track of her voluminous correspondence and papers, and she kept extensive diaries. Among the diaries were three volumes detailing her lineage; this was part and parcel of her legal strategy. In these, Lady Anne gave great credit to her mother who, through ‘great and painful industry’ was able to pry some of the essential information ‘out of the several courts and offices of this kingdom to prove the right title which her only child had to the inheritance of her father and his ancestors’. The lineage work necessary to make the claims to the Clifford estates is a clear theme of interest in other of Queen Charlotte’s historical writings.

But beyond these great volumes, Lady Anne also kept daily diaries. How Queen Charlotte came to have access to Lady Anne’s diaries is uncertain. After Lady Anne’s death there was some confusion about the disposition of the diaries and her other papers. In addition, at least one copy of her diaries may have been summarized from the longer works of which she kept multiple copies. There were at least two copies of different versions of the diaries known to be in London in the mid to late eighteenth century, and either — or another — may have been the source for the Queen’s copy. It was common for manuscripts to circulate among literary and scientific circles, and we know that George and Charlotte’s court was, among other things, just such a circle. The king clearly also had access to manuscripts that he was copying, sometimes before an author published their work.

The four pages of Lady Anne Clifford’s diary that Queen Charlotte copied cover events in the mid-1650s, beginning with ‘The 24th of Feby 1652’ and seem to include occurrences up through the autumn/fall of 1657. Lady Anne discusses her family, including children and grandchildren, her time at different properties (‘this time at Skipton 9 months’) and various conflicts. She referred to the ‘Earl of Dorset [as] the most bitter and earnest Enemy to me that ever I had, but God almighty delivered me most miraculously from all his crafty devices’. And she explicitly invoked various of her lawsuits (‘I was left to my Remedy at common law.’)

In other words, Anne was a woman in command of her realm. Given the context of the mid-seventeenth-century civil war, it is striking that Queen Charlotte found a compelling tale in a woman who was fiercely protective of her rights at law.

6. Essays on the history of England from Henry VII to George II by Princess Mary

GEO/ADD/43/17, Essays on the history of England from Henry VII to George II by Princess Mary (1776-1857) [n.d , between ?1791 and 1840]

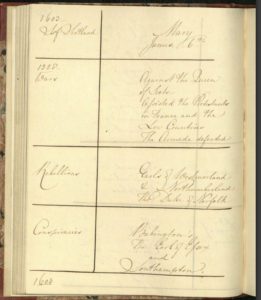

Fo. 39v of GEO Add 43/17. To read the essay in high definition, click on the image (the Essay on Elizabeth runs from fos 31r to 39v). To read the Royal Archives catalogue entry, click here.

Essays written on historical topics were commonplace at the royal court, and both the king and queen engaged in writing histories of various figures and periods. In her virtual exhibition The Essays of George III Jenny Buckley has already explored how these types of documents represent distinct collections within the Georgian Papers as well as how they were used and valued by those at the Georgian court.

Queen Charlotte and her daughters were especially interested in the histories of royal women. In particular, the lives of Elizabeth I and her rival Mary Queen of Scots provided rich opportunities for the women at the Georgian court to explore issues of political allegiance, female virtue and queenly power. Among books acquired for the royal library by Queen Charlotte were Vaelntine Greene’s bilingual Faits relatifs aux reines d’Angleterre/Acta Historica Reginarum Angliae (1786), John Whitaker’s Vindication of Mary, Queen of Scots (1790) and Lucy Aikin’s Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (1818), as well as seventeenth-century accounts including William Camden’s History of Queen Elizabeth (1688) and Thomas Heywood’s England’s Elizabeth, her life from Cradle to the Crowne (1631).

David Hume’s History of England, published in instalments between 1754 and 1761, proved a significant text for several Georgian royal women, who copied out passages into their own commonplace books, augmenting the text with their own explorations of queenliness and the role of women in the British monarchy. Queen Charlotte and princesses Mary and Elizabeth copied out extracts from Hume into several commonplace volumes covering periods of English history. The two princesses use their own copies to focus on a period covering the Elizabethan reign; a decision perhaps prompted in part by the fact they shared their names with the rival queens. Although there is little deviation between the two volumes in terms of the prose, it is in the volume produced by Princess Mary (1776-1857), the eleventh child (and fourth daughter) of Charlotte and George III, that evidence of the young royal women’s innovative and bold strategies for writing history is most visible.

Princess Mary began her commonplacing around 1791, writing out extracts from Hume and adding in her own material, collating information and arranging it in innovative ways throughout her album. The text, largely collated from Hume, covers monarchical rule in England from Henry VII to George II and draws clear lines of inheritance from earlier royal reigns and that of the Hanoverian dynasty. An inscription inside Mary’s volume, written in the hand of her sister Princess Sophia (1777-1848) for whom the album was a gift, similarly indicates the intellectual and material value of such items when exchanged among the women at court, where they were used to confirm familial and emotional ties. Sophia was closest to Mary in age and therefore the passing of this history from one sister to another may have served as a symbol not only of the distinguished and legitimate lines of the English monarchy, but as familial, sisterly inheritance situated in a more domestic and, crucially, female environments of the court.

Princess Mary’s commonplacing also signals the priorities of women at the Georgian court in being able to recall and deploy English royal histories as part of their learning. The ability to process and, crucially, recall historical information was a key component of this sort of female historiographical exercise, and signalled the genteel and elite accomplishment particularly prized in young women. Following Hume’s lead, the princess’s text is concerned only with English monarchs, likely reflecting on her own identity as daughter of George III and effectively reducing Scottish historical figures and rulers to the periphery in a move both self-reflective and highly political. Mary’s work similarly reflects a contemporary Georgian fascination with Elizabeth I and her rival Mary, Queen of Scots. In a lengthy entry for Elizabeth I, the princess sets out this historical queen’s ideal qualities as both a ruler and a woman: ‘Elizabeth succeeded her sister Mary [Tudor, daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, 1516–58] in 1558. The prudence of her conduct during her sister’s reign rendered her accession the subject of general joy – with a magnanimity truly laudable she buried all offences in oblivion.’

Throughout her commonplace, Princess Mary creates paratextual tables by collating the information in Hume’s work, summarising key themes and events, and translating sections of prose into lists and sets of data. The paratextual table that appears at the end of her account of Elizabeth I’s rule presents details of the queen of Scot’s life [fo. 39v], where she is presented as an antagonist in the English queen’s narrative. Organised by date and categories including ‘Rebellions’ and ‘Conspiracies’, Princess Mary’s table presents a narrative of Scottish defiance and responsive, but ultimately triumphant, Elizabethan power. Here, textual abbreviation becomes a deeply political act as the life and actions of the queen of Scots are diminished to a set of data serving to position her as an outsider in English history. She is quite literally excluded from the historical prose and her story is instead reduced via a system of information management to the status of a subordinate.

7. Tableau de l’Europe au commencement du 19eme Siecle

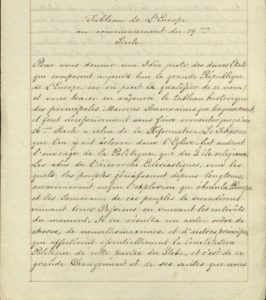

GEO/ADD43/19l: ‘Tableau de l’Europe au commencement du 19eme Siecle’ in hand of Charlotte, Queen Consort to George III [n.d. between 1800 and 1818]

To read the full document in high resolution click on the image. For the Royal Archives catalogue entry, click here.

This is a fair copy of an essay written in French and associated with Queen Charlotte’s archive. It was likely written in 1800, or shortly afterwards, and provides a history of Europe with special focus on the different historic courts of England from the Tudors to the Hanoverians. The title of the essay, ‘Tableau de L’Europe au commencement du 19eme Siecle’ (A depiction of Europe at the Beginning of the 19th Century), give a strong indication of how, for the Georgian court, historical narrative was central to notions of both British and European identity. For those in the Georgian court, much like in our own time, understanding the past was vital in order to look to and plan the future.

Set out at the start, the essay is concerned with what its author calls ‘la grande République de L’Europe’ (the grand republic of Europe) and the ‘principals Maison Souveraines’ (main sovereign houses) that govern it. In its introduction, it cites the reformation of the church in the sixteenth century as a cataclysmic event that changed forever the political landscape of Europe and Britain’s place within it. The Reformation, the author claims, set in motion ‘un autre order de choses, de nouvelles maximes, et d’autres principes, qui affectérent essentiellement la constitution politique de cette partie du Globe’ (another order of things, new maxims, and other principles, which essentially affected the political constitution of that part of the Globe).

Beginning with Henry VIII, the essay traces a history of Britain through the political and religious decisions of its monarchs. Its particular focus on the Reformation, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and the Bill of Rights demonstrates the keen interest of the Georgian court in British constitutional history. Moreover, its inclusion in Charlotte’s papers clearly shows the queen’s engagement in such histories during a period of great political change; in 1800 the Act of Union of Great Britain and Ireland was passed, inviting a shift in royal perspective.